Buddhism, since more than a century ago, has been denatured and used by those with a hidden agenda to subvert the whole world towards long-term acceptance of the anti-traditional, anti-spiritual movement. Since the Theosophists held their first ‘Parliament of the World Religions’ on the 11th September 1893 the campaign has been remarkably successful. It was the aim of the Theosophists to introduce a new world religion that would homogenise all orthodoxy, ultimately replacing revealed religion with a counterfeit designed to propagate Western values and idealism. From there emerged Neo-Advaita or Neo-Hinduism, which is defined by its subversive propagation of that same idealism under the cover of its teaching Hindu studies to the West. This disguised anti-traditional movement first gained popularity through the very lucrative alliance between Swami Vivekananda and the Theosophists.

Let us go back to the beginning. Once a new, psychologised Buddhism had been introduced as a viable support to the ambitions of the Theosophists, the de-natured, tranquilised Buddhist panacea was eagerly taken up by psychologists in all areas of the theoretical science. According to an article by Seth Zuihõ Segall, ‘Buddhism and Psychology’,

Over the past century-and-a-half psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts have analysed, pathologised, misinterpreted, appreciated, assimilated, adapted, and or converted to Buddhist ideas and practices. At the same time, psychological approaches to Buddhism have led to ‘naturalised’ and ‘psychologised’ forms of contemporary Buddhist practice, especially in ‘convert’ Buddhist communities.[1]

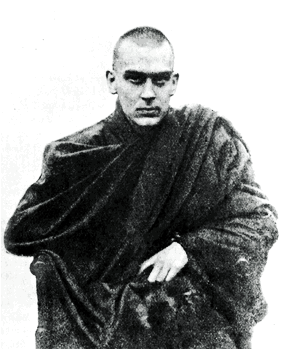

Left: Allan Bennett, friend and mentor to Aleister Crowley.

Left: Allan Bennett, friend and mentor to Aleister Crowley.

The powerful though intensely negative Shunyavada or No-Self ‘void’ theory all but swept away first the occultists, already willing to play host to any attack on tradition.[2] Our story begins in the late nineteenth century, while Vivekananda was taking centre stage in the anti-traditional campaign of the Theosophists. The notorious black magician and drug addict Aleister Crowley at first rejected Buddhism on the grounds that it is pessimistic as demonstrated by the Four Noble Truths, which he summed up as ‘Existence is Sorrow’. Allan Bennett, his friend and spiritual mentor in the Neo-Rosicrucian Order of the Golden Dawn, also a Theosophist, sensibly refused to accept Crowley’s absurd claim to be the New World Teacher of a ‘New Aeon’. Bennett, who was ordained with the Buddhist monk name Bhikkhu Ananda Metteyya, continued to campaign along with his Theosophist friends to establish Buddhism in England and Ireland.[3] It is curious to relate that later in life Crowley leaned increasingly to an orientalist interpretation of his Book of the Law, which was produced by means of spiritism when it was not simply fabricated by one who sought fit to personally identify himself with the Antichrist. This is so much so that one might even say Crowley became a crypto-Buddhist.

This ‘secret Buddhism’ was facilitated quite early on when another friend of Crowley contrived to interpret certain lines from the aforesaid book with the mathematical pseudo-formula 0 = 2. Put in more exact terms, this is expressed as the formulaic (+1) + (-1) = 0. The problem with this affirmation of ‘nothing’ or Buddhistic ‘emptiness’ is that it is not correct—the equation does not work, as any mathematician will tell us. The formula actually adds to 1 and that is all. A positive (+1) is not negated by having a negative value added to it.[4] The error is very much in keeping with the arguments of Buddhism though, which is where Crowley derived the false notion that two equal and opposite things cancel each other out leaving zero. However, they do not cancel out—which is a metaphysical impossibility otherwise they would both be nothing to start with. Instead, two equal and apparently opposite things are resolved in their transcendent, unitive principle. The false ‘cancelling’ argument has been used in Buddhism as a refutal of all else but the human mind. While insisting that the mind, as with everything else, is nothingness or ‘emptiness’, as with the Shunyavada ‘void’ theory, integral to that path in all its manifestations, Buddhists use this empty notion to deny that anything exists as a higher principle to the mind. Thus, in the denial, they actually affirm the mind as sole reality, even if it is ‘empty’. So according to them, it really is all nothing. Crazy as it sounds, this is the essence of Shunyavada Buddhism, though we will freely admit that in no tradition, even a heterodox one like Buddhism, should the teaching be confused with the goal.

In more recent times than those of Crowley and his disciples, the same erroneous lines of thought—ideas that nonetheless have great appeal to the ‘men of reason’ who cannot reach any further than the narrow limitations of their modernist ideologies—was a considerable influence on the occult fantasist and orientalist Kenneth Grant. No doubt for reasons of gaining an easy influence over his would-be followers, he applied the ubiquitous Shunyavada ‘void’ theory to the classical Qabalistic qliphoth or ‘shells of dead matter’, as moderns have interpreted this. The idea is that demons are ‘masks of emptiness’. It is therefore worthwhile to conjure demons, according to this thesis, with names taken from any source imaginable or available so as to acquire some sort of knowledge concerning reality or space—or ‘something’, as the goals of Grant’s invented tradition were always placed in extremely obscure and usually self-contradictory terms. When he was most clear on the great purpose of his peculiar brand of occult experimentalism, he defined it for members of his Typhonian Order as the ‘dissolution of all world governments’. Laudable as that might seem, the plan actually involved facilitating cracks or ‘fissures’ in the psychic or subtle defences of the world so that demonic forces or the Qliphoth as they are termed in the Qabalah could claim the earth and return it to conditions resembling the most nightmarish fantasies of the horror fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft. Owing to this deliberate (or strategic) obscurity—for there is in fact really ‘nothing’ at all behind Grant’s skewed reasoning—those who followed Grant have tended to pursue very ordinary, profane fetishism, which came about through the heavy sexualisation of all Grant’s fantasies, usually focussing on onanistic voyeurism. Others have watered down the pseudo-doctrine until it becomes no different from New Age popular psychological theories such as ‘exploring your dark side’ for the purpose of becoming a better human being; such simplistic morality lurks wherever such bourgeois manipulation gains a hold on the kind of minds susceptible to it.[5]

It is interesting to note how pervasive the 0 = 2 confabulation has proved to be, for Swami Sarvapriyananda, Minister of the Vedanta Society of New York, has mentioned it while giving a lengthy and elaborate justification of Buddhism. He presumably has no idea it is sourced from the works of Crowley as he cited a contemporary Western philosopher as its origin. He had also mentioned the Buddhistic ‘cancellation’ argument against all higher principles, a line of thought that he seems to find strangely compelling, so much so that he successfully completed a course in Buddhism at the prestigious Harvard University. The Swami seems to have been led through his association with postermodernist academia to go so far as tearing out the roots of his own lineage and tradition, publicly declaring that the ancient sages Gaudapada and Adi Shankaracharya were ‘wrong’ when they rejected the Buddhistic ‘void’ theory. A weak argument against the accusation of nihilism that the classical sages made against the Shunyavada ‘void’ has been suggested by the Swami, though it is nothing new, on grounds that the meaning is not ‘nothing’ but ‘no-thing’. This became very popular among the followers of Kenneth Grant, decades previously.

Swami Sarvapriyananda has also used this argument in his defence of Buddhistic emptiness, in which he has falsely claimed—to the delight of the postmodernist pundits—that there is really no difference between Shunyavada and Advaita Vedanta or at least, the goal is the same and that Shunyavada is a “mirror image” (in his words) of Advaita Vedanta. As a ‘satanic’ inversion of Advaita Vedanta, the mirror image analogy works but it seems the Swami is as yet unable to see that the inversion of a doctrine is in no way equal to the doctrine it is falsifying, and that furthermore the goal is not liberation but enslavement to the deepest illusion of all, that of the negation of the Self (Atma). For this reason Buddhism has been called ‘No-Self’, an entirely negative point of view as it denies all metaphysical principial reality. As for the ‘no difference’ between Advaitan Non-dualism and the Buddhist No-Self void theory, this amounts to saying there is no difference between an incomplete heterodox doctrine and a complete metaphysical one.

The obvious shortcoming of the ‘no-thing’ apology is that it only negates all objects of mind. That means there is only pure subjectivity as the Real, so long as we do not take that to mean mere psychological subjectivity. The Shunyavada ‘void’ School, however, rejects subjectivity as keenly as it denies objectivity! The notion that Buddhism and Advaita are then either comparable or even identical is also impossible on these grounds. An inevitable consideration now arises: if it is all about ‘no things’, no objects, what need do we have of Buddhism? We can do that with Ashtanga Yoga very well and it will also take us much further. Unlike the populist, westernised forms of Buddhism, we are not there required to adopt the profane attitude of atheism or indeed any such narrow-minded, heterodox teachings.

In Swami Sarvapriyananda’s small book Fullness and Emptiness: Vedanta and Buddhism, it is claimed that Advaita and Buddhism ‘spring from the same source’, while grossly misrepresenting then denouncing traditionalists for saying the same thing only more exactly. The fact that Buddhism was always a heterodox darshana is entirely omitted from this work, which typifies the approach taken by Neo-Hinduism, a term that expressly denotes the Western influence. For example, anything that does not fit with the core political and social agenda of the postmodernists is relegated to an ‘Old Hinduism’, as though antiquity counts against it automatically without any need of further explanation. The scholarly Foreword to the book, though not written by Swami Sarvapriyananda, makes an unfounded, malicious attack on traditionalism in two places, deliberately inverting the point of view of the Perennialist school of thought founded by the master metaphysican René Guénon. While this is no doubt due to incomprehension of the Primordial Tradition thesis put forward by Guénon, there is no justification for such outright lies.

However, the tactic of misrepresenting or even completely inverting what an author has written based on traditional doctrine is alway used by the anti-traditional movement to condemn something without need to supply evidence or reasoning.[6] If any evidence were needed for the ‘satanic’ inversion of spiritual truth employed here, it is declared in this same text that anciently, ‘spiritual experience’ actually followed establishment of a reasoned or rational point of view, instead of reason following a spiritual influence, as it properly should be and always is in the case of genuine metaphysical doctrines.[7]

Finally, the title of Sarvapriyananda’s book, Fullness and Emptiness: Vedanta and Buddhism, once again asserts the ‘mirror image’ view, while ignoring the fact that a totality or ‘fullness’ (Sanskrit purnam), which has its equivalent in the classical Greek pleroma, cannot be either a complement or an opposition to ‘emptiness’, which is pure negation. From the metaphysical point of view, if we were to accept fullness and emptiness then what happens is that emptiness, being nothing, is removed and only Brahma, the fullness, remains. This however is automatically limited by the hypothesis as it only extends to the principle of Pure Being, and Advaita goes one step further than even that. In this way, Buddhism, or at least Buddhism understood like this, is like Ashtanga Yoga but stopping in the beginning stages, where the content of the mind is eliminated by the practice and yet nothing further is realised. From the point of view of yoga practice, it is very hazardous for the practitioner.

Pervasive Buddhism: Notes

1. University of St Andrews, 6th June 2024: Article

2. Occultism is a field that was once marginalised but that has recently been declared acceptable by the new generation art establishment. To do that, they have subverted and misrepresented the work of historical artists, to make it seem as if they were pioneers in the Neo-Socialistic idealism that now pervades the fields of both art and literature. See our article, ‘Art and the Occult’:

https://www.ordoastri.org/colquhoun-ithell-surrealism-occult/

3. The anti-traditional plans of Bennett’s Theosophist cohorts included the ‘liberalisation of Christianity’. See René Guénon, Theosophy: History of a Pseudo-Religion.

4. Curiously, the formulaic 0 = 2 can be made to work but none of its advocates have understood how because they wanted to affirm the Buddhistic ‘void’. If the Zero is taken as metaphysical Zero, which means it does not represent quantity but is an analogy for the supreme principle, which is unmanifest, then it may be understood that the unmanifest contains all manifest and unmanifest possibilities.

5. See the third section of our book, Thirty-two paths of Wisdom [Ordo Astri].

6. Perennialism is somewhat inaccurately equated with Traditionalism. Guénon himself would not describe himself as either Perennialist or Traditionalist, and said there is a difference between Traditonalism and Tradition. Perennialism is ‘that which endures’.

7. It must be mentioned also that there are some who deliberately confuse the pure intellectual (and spiritual) Perennial Wisdom of Guénon with a different and political ‘perennialism’, which Guénon had no part in whatsoever. Postmodern scholars, on the other hand, always have a social-political agenda at the core of their obfuscation for they reduce all spirituality to ‘ordinary life’. For the same reason they reduce all ancient doctrines to ‘philosophy’, so it is no different to the theories and speculation that they build their careers on. All traditional scriptures insist that the knowledge is from a non-human (or supra-human) source—but that is well beyond the reach of academics to comprehend. On the contrary, it merely enrages them and they use everything at their disposal, including outright lies, to suppress the truth.

The photograph of Allan Bennett is thought to originate from early archives of the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland and later the Theosophical Society. Original publication: Bennett, Allan; Metteyya, Ananda. The Religion of Burma and Other Papers. A M S Press, Inc. ISBN 9780404167905. Immediate source: Archive Library.

© Oliver St. John 2025

Books by Oliver St John

Podcast Metaphysics of the Real: RSS.com

On RSS you can listen on 15 platforms, including Apple, Spotify, Amazon, etc.

Metaphysics of the Real podcast on YouTube Channel